Abstract

Introduction: Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) significantly reduces the risk for malignant diseases like cervix, anal, or penile cancer. However, although vaccination rates are rising, they are still too low mirroring a lack of disease awareness in the community. This study aims to evaluate knowledge about HPV vaccination as well as the vaccination rate among German medical students. Material and Methods: Medical students were surveyed during a German medical students’ sports event. The self-designed survey on HPV vaccination consisted of 24 items. The data collection was anonymous. Results: Among 974 participating medical students 64.9% (632) were women, 335 (34.4%) were male and 7 (0.7%) were nonbinary. Mean age was 23.1 ± 2.7 (± standard deviation; range 18–35) years. Respondents had studied mean 6.6 ± 3.3 (1–16) semesters and 39.4% (383) had completed medical education in urology. 613 (64%) respondents reported that HPV had been discussed during their studies. 7.6% (74) had never heard of HPV. In a multivariate model female gender, the knowledge about HPV, and having worked on the topic were significantly associated with being HPV-vaccinated. Older students were vaccinated less likely. Conclusions: Better knowledge and having worked on the topic of HPV were associated with a higher vaccination rate. However, even in this highly selected group the knowledge about HPV vaccination was low. Consequently, more information and awareness campaigns on HPV vaccination are needed in Germany to increase vaccination rates.

Introduction

The human papillomavirus (HPV) commonly causes benign and malignant diseases. While HPV subtype 6 or 11 is responsible for benign genital warts (e.g., condylomata acuminata), an infection with high-risk HPV-types 16, 18, 31, or 45 can lead to malignant diseases of the cervix, anal, pharynx, or penis [1].

The most effective way to protect oneself against the most common high-risk types of HPV is the vaccination before the first sexual activity [2, 3]. For girls, the German Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) issued its recommendation in 2007, whereas the vaccination for boys was finally recommended in 2018 [4]. In comparison with European countries, HPV vaccination rates in Germany are very low [5]. Furthermore, according to a study with a representative sample of the German population, awareness of HPV and HPV vaccination in the German population is significantly lacking [6].

Preventive measures are the gold standard to reduce the risk and prevalence of diseases. Accordingly, educational campaigns are of particular importance in conveying knowledge and promote prevention. Despite their importance, the social perception of such campaigns is underrepresented [7]. Also, young peoples’ perception and basic understanding of prevention in general seems to be gender dependent to a large extent. Within this context, the knowledge of young people about testicular tumors and testicular self-examination has been demonstrated to be very low [8]. A comparison of testicular and breast self-examination showed that girls examined their breasts more often than boys examined their testicles [9].

The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge about the HPV vaccination rate in a highly selected target group, supposed to be aware and well informed about these topics. We hypothesized that knowledge on HPV would be good among medical students and expected a high vaccination rate. Moreover, we expected both to be superior among female students.

Material and Methods

Study Population and Design

A sports event for medical students was held at Obermehler-Schlotheim airfield in Germany from the 1st to the September 4, 2022. During this sports event members of Prevention and Advocacy of Testicular Education e.V. (PATE) distributed the survey to medical students. PATE is a nonprofit organization that provides information on benign and malignant diseases in young men (www.pate-hodenkrebs.de). In addition to diseases of the testicles and epididymis, PATE’s prevention and education activities also focus on HPV. PATE also founded a support group for testicular tumor patients and coordinates the exchange. The educational work is carried out by volunteers within the framework of lectures, seminars, and social media posts. Moreover, scientists from the fields of urology, psycho-oncology, uro-oncology, medical ethics, and basic research accompany the work of PATE and evaluate the educational work.

Questionnaire

Building on previous work [8], the members of PATE and the authors of this study developed a 17-item survey. This draft was optimized after feedback of 17 volunteers who tested the survey. Finally, the questionnaire showed good face validity [10]. The survey was divided into two parts. The first part addressed general information about the participants, such as age, gender, home university, and semester of medical education. The second part surveyed the knowledge of HPV vaccination and whether participants were HPV-vaccinated (online suppl. material; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000536257). The collection of data was anonymous. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Human Medicine of the Philipps-University Marburg (file number: 127/22).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as frequencies and proportions. To compare groups, we used χ2 and t tests. A logistic regression was used to predict students’ HPV vaccination status. The significance level was determined at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM, Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The questionnaire was completed by 974 medical students. Of these, 632 (64.9%) were female, 335 (34.4%) were male and 7 (0.7%) were nonbinary. The mean age was 23.1 ± 2.7 (range 18–35) years. On average male students were 8 months older than their female peers. Participants had studied mean 6.6 ± 3.3 (range 1–16) semesters. 383 (39.4%) had taken Urology as a subject during their medical education and 613 (64%) already worked on the topic of HPV vaccination, whereas 74 (7.6%) had never heard of HPV.

597 (61.7%) of the students were HPV-vaccinated. The vaccination rate was significantly higher among females than males (82% vs. 24%, p < 0.001). Accordingly, significantly more men (44%) reported that their partner was vaccinated compared to a 12% partner vaccination rate reported by female students (p < 0.001, Table 1).

Comparison of age and HPV vaccination status between women, men, and nonbinary

| . | Women (N = 632) . | Men (N = 335) . | Nonbinary (N = 7) . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 22.9±2.5 | 23.6±3.0 | 22.9±2.3 | <0.001 |

| Vaccination rate, n (%) | 514 (82) | 79 (24) | 4 (57) | <0.001 |

| Partners’ vaccination rate, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 74 (12) | 147 (44) | 3 (43) | <0.001 |

| No | 343 (54) | 73 (22) | 3 (43) | |

| Don’t know | 138 (22) | 84 (25) | 0 | |

| No partner | 77 (12) | 31 (9) | 1 (14) | |

| . | Women (N = 632) . | Men (N = 335) . | Nonbinary (N = 7) . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 22.9±2.5 | 23.6±3.0 | 22.9±2.3 | <0.001 |

| Vaccination rate, n (%) | 514 (82) | 79 (24) | 4 (57) | <0.001 |

| Partners’ vaccination rate, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 74 (12) | 147 (44) | 3 (43) | <0.001 |

| No | 343 (54) | 73 (22) | 3 (43) | |

| Don’t know | 138 (22) | 84 (25) | 0 | |

| No partner | 77 (12) | 31 (9) | 1 (14) | |

Impact of Knowledge about HPV

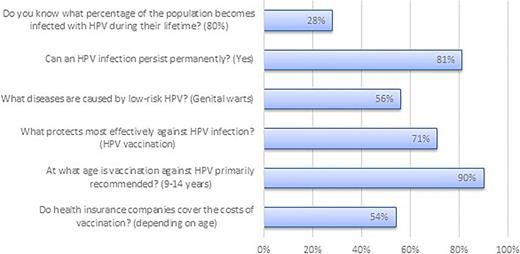

Most students responded correctly on questions about the recommended age of vaccination (90%), the possibility of protection through vaccination (71%), and the persistence of HPV once infected (82%, Fig. 1). About half of the students knew diseases caused by low-risk HPV (56%) and the regulations of the German insurance system (54%). Only 28% knew about the lifetime risk of HPV (Fig. 1).

In a gender comparison, significantly more women knew the correct answers for questions on age of vaccination (94% vs. 83%, p < 0.001) and cost coverage (58% vs. 49%, p = 0.009). In contrast, more men answered correctly about the lifetime risk of HPV infection (26% vs. 3%, p = 0.024). The number of 7 nonbinary participants was too small to draw meaningful statistical comparisons. In Table 2 comparisons between students that have versus have not worked on the topic of HPV vaccination are described.

Comparison between students that have versus have not worked on the topic of HPV vaccination during their study

| . | Worked on the topic HPV, n = 613 (64%) . | Not worked on the topic HPV, n = 352 (36%) . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women, n (%) | 397 (63) | 231 (66) | 0.89 |

| Age, years | 23.9±2.4 | 22.0±2.7 | <0.001 |

| Semester | 8.3±2.7 | 3.8±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Do you know what percentage of the population becomes infected with HPV during their lifetime? (80%), n (%) | 231 (38) | 43 (12) | <0.001 |

| Can an HPV infection persist permanently? (Yes), n (%) | 554 (90) | 230 (65) | <0.001 |

| What diseases are caused by low-risk HPV? (Genital warts), n (%) | 440 (72) | 101 (29%) | <0.001 |

| What protects most effectively against HPV infection? (HPV vaccination), n (%) | 461 (75) | 221 (63) | <0.001 |

| At what age is vaccination against HPV primarily recommended? (9–14 years), n (%) | 573 (95) | 290 (82) | <0.001 |

| Do health insurance companies cover the costs of HPV vaccination? (depending on age), n (%) | 382 (62) | 145 (41) | <0.001 |

| . | Worked on the topic HPV, n = 613 (64%) . | Not worked on the topic HPV, n = 352 (36%) . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women, n (%) | 397 (63) | 231 (66) | 0.89 |

| Age, years | 23.9±2.4 | 22.0±2.7 | <0.001 |

| Semester | 8.3±2.7 | 3.8±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Do you know what percentage of the population becomes infected with HPV during their lifetime? (80%), n (%) | 231 (38) | 43 (12) | <0.001 |

| Can an HPV infection persist permanently? (Yes), n (%) | 554 (90) | 230 (65) | <0.001 |

| What diseases are caused by low-risk HPV? (Genital warts), n (%) | 440 (72) | 101 (29%) | <0.001 |

| What protects most effectively against HPV infection? (HPV vaccination), n (%) | 461 (75) | 221 (63) | <0.001 |

| At what age is vaccination against HPV primarily recommended? (9–14 years), n (%) | 573 (95) | 290 (82) | <0.001 |

| Do health insurance companies cover the costs of HPV vaccination? (depending on age), n (%) | 382 (62) | 145 (41) | <0.001 |

Students who had already dealt with HPV during their studies (older, higher semester) scored significantly better than those who have not worked on HPV in all questions. Table 3 presents the results of a logistic regression to predict the probability of being HPV-vaccinated. Predictor variables were gender, having worked on the topic of HPV, age, and the sum of all correct answers to the knowledge questions (knowledge HPV).

Logistic regression to predict the probability of being HPV-vaccinated

| Predictor . | Odds ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 14.3 | 10.2–20.0 | <0.01 |

| Worked on topic HPV | 1.64 | 1.11–2.42 | 0.01 |

| Age | 0.86 | 0.80–0.92 | <0.01 |

| Knowledge HPV | 1.22 | 1.07–1.38 | <0.01 |

| Predictor . | Odds ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 14.3 | 10.2–20.0 | <0.01 |

| Worked on topic HPV | 1.64 | 1.11–2.42 | 0.01 |

| Age | 0.86 | 0.80–0.92 | <0.01 |

| Knowledge HPV | 1.22 | 1.07–1.38 | <0.01 |

Besides female gender the knowledge about HPV and having worked on the topic were significantly associated with being HPV-vaccinated. Older students were vaccinated less likely.

Besides female gender the knowledge about HPV and having worked on the topic were significantly associated with being HPV-vaccinated. Older students were vaccinated less likely.

Discussion

More knowledge about HPV vaccination is associated with a higher vaccination rate. Besides, female students knew more about the HPV topic in comparison to male students. HPV thematized in medical school increases the knowledge about HPV among medical students. At the same time, knowledge about HPV among medical students in our study was surprisingly low. For example, only 38% of the students, who dealt with the HPV topic knew that approximately 80% of the population becomes infected with HPV during their lifetime.

This knowledge gap was also seen in another study that investigated German-speaking medical schools of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. The study showed that knowledge on HPV was low among the participants and increased by the year of study [11]. This trend was also reflected in international studies. An American study showed a lack of knowledge on HPV and the HPV vaccine among medical students in the US which decreased by the year of study [12]. A cross-sectional study from Turkey, where the survey has been distributed via social media, showed comparable results [13]. In a gender comparison of HPV knowledge, many studies show, that female students are better informed about the topic of HPV than male students. Female students answered more questions on HPV correctly in comparison to male students [14, 15]. This was also evident in our data, in which female students gave significantly more correct answers about HPV and HPV vaccination compared to male students (e.g., age of vaccination 94% vs. 83%, p < 0.001) and cost coverage of the vaccination (58% vs. 49%, p = 0.009). This illustrates that, with an already low level of knowledge about HPV, male students know even less about the topic.

The HPV vaccination has been recommended by the Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) in Germany for several years, but HPV vaccination rates in the German population are low (47% female and 5% male teenagers) [16]. In our sample, medical students were more frequently vaccinated against HPV than the general population. But even according to our data, vaccination rates were significantly different depending on gender. Female students were vaccinated more than 3 times as often compared to male students (82% vs. 24%). In contrast, the reported HPV vaccination rates of the partners (47% for female partners and 12% for male partners) are in the same range as can be expected in the normal population. A study that evaluated the HPV vaccination coverage among German girls as the first follow-up survey of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KIGGS Wave 1) showed that the complete vaccination rate was 39.5% and increased with the age of the girls [17]. The KIGGS Wave 2 follow-up study after 5 years showed a stable HPV vaccination coverage among German girls [18]. A study that examined boys in Germany after the STIKOs HPV vaccination recommendation in 2018 showed that the initial HPV vaccination rates of boys were comparable in the first months of the recommendation to those of girls, but declined steadily from year to year – presumably due to the Corona pandemic [19].

The low nationwide HPV vaccination rate illustrates the urgent need for an increase in Germany. This becomes even more evident in a European comparison of the HPV vaccination rates, in which Germany ranks low [20]. The European countries with the highest vaccination coverage have either a high population acceptance of the HPV vaccines or school-based vaccination programs [21]. A suggestion for improvement from experts to optimize HPV vaccination rates is to take advantage of school vaccination, promotion of participation in the J1 examination, and an introduction of reminder and invitation systems [22]. The J1 examination is an adolescent health check-up in Germany whose participation of adolescents is very low [23]. Also, the integration of social media showed potential to impact awareness, knowledge, and attitudes of some people toward HPV and HPV vaccination [24]. A systematic survey of vaccination coverage among students (age group 12–16 years) shows that the primary health care system does not reach young people sufficiently and suggests that the public health service should support to identify vaccination gaps [25]. Prevention campaigns have already shown their potential to increase knowledge and awareness on other diseases [7, 26].

Despite several years of STIKO recommendations, the results on knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination among German medical students are very low. The focus of the individual faculties on the topic of HPV could certainly be deepened. Independently of this, general governmental and voluntary educational work is needed. Therefore, prevention campaigns in particular have a special role to play in education. Moreover, prevention work must become more present and involve more stakeholders. In a study by Karschuck et al. [27] digitization in the context of patient events showed that two-thirds of the participants surveyed were in favor of hybrid formats. Accordingly, the German Society of Urology (DGU) founded the Urological Foundation for Health gGmbH in 2021 to intensify the communication of urological topics to the public. The foundation is gradually building up an information and service portal for affected persons and interested laypersons (www.urologische-stiftung-gesundheit.de).

Medical training on this topic is individually fed into the curriculum at German medical faculties. The information on the curriculum of the individual medical faculties and the response rate of the participation are missing in our data. Besides, the examined sample is not representative for Germany. In addition, the low level of knowledge about HPV in a very positively selected group of medical students suggests an even significantly poorer level of knowledge in the general population. Another limitation of our study was that we could not determine a questionnaire’s return rate. The reason for this was that we could not determine how many visitors were at the study booth. Further studies on this topic must be conducted continuously to determine the trend in HPV knowledge and HPV vaccination in Germany.

Conclusion

This study showed that even in a positively selected collective of German medical students, the knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination is low. To improve vaccination rates in Germany, PATE will continue its work on rising public awareness on young men’s health, especially on HPV and the HPV vaccination.

Acknowledgments

Part of this study was presented at the Annual Meeting of the German Association of Urology and the Annual Meeting of the Southwest German Association of Urology in 2023. PATE e.V (www.pate-hodenkrebs.de). developed the questionnaire. Special thanks to Sati Babayigit for her personal support.

Statement of Ethics

The data collection was anonymous. The participants gave verbal consent after being informed about the study. No written informed consent was obtained. The ethical approval for this procedure and the study was given by the Ethics Committee of the Philipps-University Marburg in accordance with local and national guidelines (file number: 127/22). The study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Huber reports grants and nonfinancial support from Intuitive Surgical, Takeda, Janssen, Apogepha, and Coloplast outside the submitted work. Moreover, he is member of the medical board of the Urological Foundation for Health. All other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

The authors received no funding for this project. There are no financial disclosures from any author.

Author Contributions

Cem Aksoy: project development, data collection, data management, and manuscript writing/editing. Andreas Ihrig: data analysis and management, and manuscript writing/editing. Annika Schumann: data management and manuscript writing/editing. Laila Schneidewind, Hendrik Heers, Luka Flegar, Philipp Reimold, and Philipp Karschuck: manuscript writing/editing. Marianne Leitsmann and Aristeidis Zacharis: project development and manuscript writing/editing. Johannes Huber: project development, data analysis, and manuscript writing/editing.

Additional Information

Aristeidis Zacharis and Andreas Ihrig contributed equally as last authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to practical and financial reasons but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.