Abstract

The symptomatic nephroptosis of a kidney transplant is a rare and potentially fatal complication and requires fast diagnosis and treatment. In this report, we describe a case in which intermittent symptomatic hydronephrosis and an increase of the creatinine levels were the leading symptoms of nephroptosis. Moreover, we describe the diagnostic procedures and the successful minimal-invasive treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a symptomatic transplant nephroptosis with consecutive intermittent hydronephrosis and without complications of perfusion solved with a minimal-invasive approach.

Introduction

With an incidence of 5–10%, surgical complications after kidney transplantation are a common issue and bear the risk to negatively affect transplant function [1]. Although the spontaneous change in position of the transplant is rare, it can cause fatal complications that might lead to transplant loss [1, 2]. To the best of our knowledge, the following report describes the first case of transplant nephroptosis resulting in a symptomatic hydronephrosis of the transplant.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old male patient, suffering from terminal renal failure due to an IgA nephropathy, received a kidney donation from his wife. The kidney transplantation was performed AB0-incompatible, with application of rituximab and several plasmapheresis proceedings in preparation. The immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate-mofetil, and methylprednisolone. The right donor kidney owned 1 vein, 1 artery, and a long ureter. It was transplanted in an extraperitoneal open approach into the right iliac fossa, with a fenestration of the peritoneum to avoid lymphocele formation.

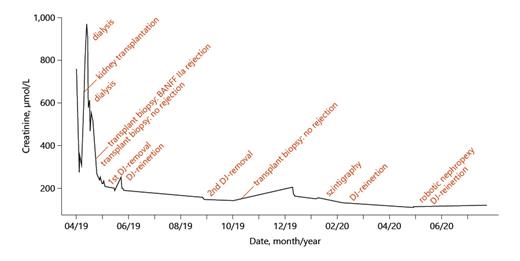

The kidney initially showed an adequate urinary excretion resulting in a decrease of the creatinine levels (Fig. 1). On the next day, however, the creatinine levels increased again. A transplant biopsy on the 5th postoperative day showed a BANFF IIa rejection, which required i.v. methylprednisolone, thymoglobulin, and plasmapheresis. Furthermore, a dialysis was necessary on the 12th and 14th postoperative days due to hypervolemia and increasing creatinine values. A second transplant biopsy on the 22nd postoperative day excluded a rejection. Over the course of the next days, the creatinine levels dropped, and the patient was discharged 10 days later with a creatinine value of 202 μmol/L. After removal of the ureteral stent, a stable and asymptomatic mild hydronephrosis with a stable creatinine appeared.

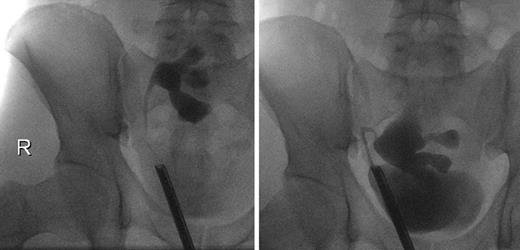

On the 51st postoperative day, the patient presented an elevated creatinine of 241 μmol/L and a stable hydronephrosis, so that a stent insertion was necessary. The retrograde ureteropyelography showed no pathologies (Fig. 2), and the creatinine levels decreased afterwards. The perfusion of the kidney was adequate. The removal of the ureteral stent was successfully performed 3.5 months later. In the 9th postoperative month, a scintigraphy was performed and showed a functional obstruction of the kidney transplant, so that we initially refrained from further interventions.

Ureteropyelogram 6 weeks (left) and 9 months (right) after kidney transplantation.

Ureteropyelogram 6 weeks (left) and 9 months (right) after kidney transplantation.

The following ultrasound controls showed a progredient hydronephrosis, requiring a reinsertion of the ureteral stent. Furthermore, the patient reported a hypermobility of the transplant in his pelvis. The intraoperative ureteropyelography confirmed this by showing a hypermobility of the kidney depending on the degree of bladder filling (Fig. 2). According to this diagnosis, a robot-assisted transplant nephropexy was performed. Further sonographic controls showed a stable pelvic ectasia with stable creatinine levels around 111 μmol/L.

Surgery

The operation was performed with the Da-Vinci-Surgical-System® (SI-Version; Intuitive Surgical, 2009) in a light Trendelenburg position. We chose a transperitoneal approach with the camera trocar inserted 5 cm above the umbilicus and 2 more trocars on both sides 5 cm above the level of the umbilicus. By using one of the 2 working trocars for the insertions of suturing material, a fourth incision for an assistant trocar was unnecessary.

In the Trendelenburg position, the kidney dropped cranially and stretched the ureter. In this position, the perirenal capsule of the upper pole was fixed to the lateral peritoneum with 4 vicryl 2-0 sutures. We further performed an arched incision into the ventral peritoneum beginning from the internal inguinal ring. After preparation of the cavum Retzii and the peritoneum of the urinary bladder, it was flapped over the transplant and fixed cranially of the transplant. Fixation stitches were performed to the peritoneum to attach the “safety belt” to the ventral aspect of the kidney transplant. Total surgery time was 86 min, and estimated blood loss was 20 mL (online suppl. video, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000518133).

Discussion

This is the first report of a symptomatic transplant nephroptosis with consecutive intermittent hydronephrosis and without complications of perfusion. Moreover, it is the first successful minimal-invasive treatment. Most of the case reports describe acute hypoperfusion as a severe consequence of a renal pedicle torsion. This was reported for both intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal kidney transplants [2-6]. Similar to our case report, Dosch et al. [7] reported an intermittent acute renal injury and hypertension in a pancreas- and renal-transplanted patient due to intermittent pedicle torsion of the transplanted kidney.

The most frequent symptoms of nephroptosis were acute renal insufficiency with elevation of kidney retention parameters, decreasing urinary excretion, and hypoperfusion of the transplant in the duplex sonography [2-6]. This complication has been described shortly after transplantation as well as up to 10 years later [2, 4].

However, in this case, duplex sonography showed a good perfusion at all times. Only the intermittent hydronephrosis gave a hint toward a mechanical problem. Furthermore, the first ureteropyelography before reinsertion of the ureteral stent showed no abnormalities, making it difficult to establish an accurate diagnosis. Finally, the combination of the patient’s subjective feeling of hypermobility of the transplant and lacking evidence of ureter complications in the ureteropyelography lead us to the idea of a possible nephroptosis. The described case is also extraordinary because usually local inflammatory reactions after transplantation cause immediate fixation of the transplant kidney in the surrounding tissue and, if revision surgery is necessary, access to the transplant kidney is often difficult after only a few weeks. While the use of a peritoneal flap to fix the allograft became common in transperitoneal robotic transplantations [8], this is not established in open kidney transplantations. It is possible that migration of the transplant kidney through the peritoneal fenestration into the intraperitoneal cavity may have caused the hypermobility. As a consequence, size and location of the peritoneal fenestration should be chosen considering this problem.

In summary, the intermittent nature of the hydronephrosis and elevation of creatinine levels together with the duplex sonography are the most important diagnostic methods to detect a nephroptosis if the sonography is being performed in various positions. Given the rarity of this event, prophylactic nephropexy is likely to only be discussed in very particular circumstances. Nevertheless, hypermobility of the allograft should be considered in cases of intermittent hydronephrosis, absence of perfusion pathologies, and clinical abnormalities. The treatment as described is straightforward, easy to perform, and bears little stress for the patient.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Ulrich Zimmermann for his technical support for the video.

Statement of Ethics

The authors declare to have conducted the above described diagnostical methods and treatment in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The patient gave informed written consent to publish his case, images, and recordings.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This case report, including images and recordings, was carried out without funding.

Author Contributions

Elena Nikitin extracted the patient information, wrote the manuscript, and generated the graph showing the course of creatinine of the patient. Johannes Huber contributed to the diagnostic of the nephroptosis of the patient and performed the surgery. Further, he revised the manuscript. Christian Thomas contributed ideas, revised the manuscript, and was involved in decision-making concerning the diagnostic and treatment of the patient. Juliane Putz supervised the project, contributed ideas and references to the manuscript, and revised it. Moreover, she is an important reference person to the patient and was involved in his diagnostical and therapeutical procedures.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy and ethical concerns the data cannot be made available.